COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS

Edward Weston’s life is of near mythic proportions: a series of love affairs, sojourns to Mexico with exotic Tina Modotti, a Spartan lifestyle — truly the elements of which legends are made. Yet behind the often exaggerated stories and tales of the frequently misjudged artist stands a man driven by passion, deep emotion, and a unique eye. Although introspective, he was not the dark, brooding, bohemian intellectual and lover as he was often portrayed, but a man possessed by a relentless drive to seek beauty, perfection, and emotionally charged images.

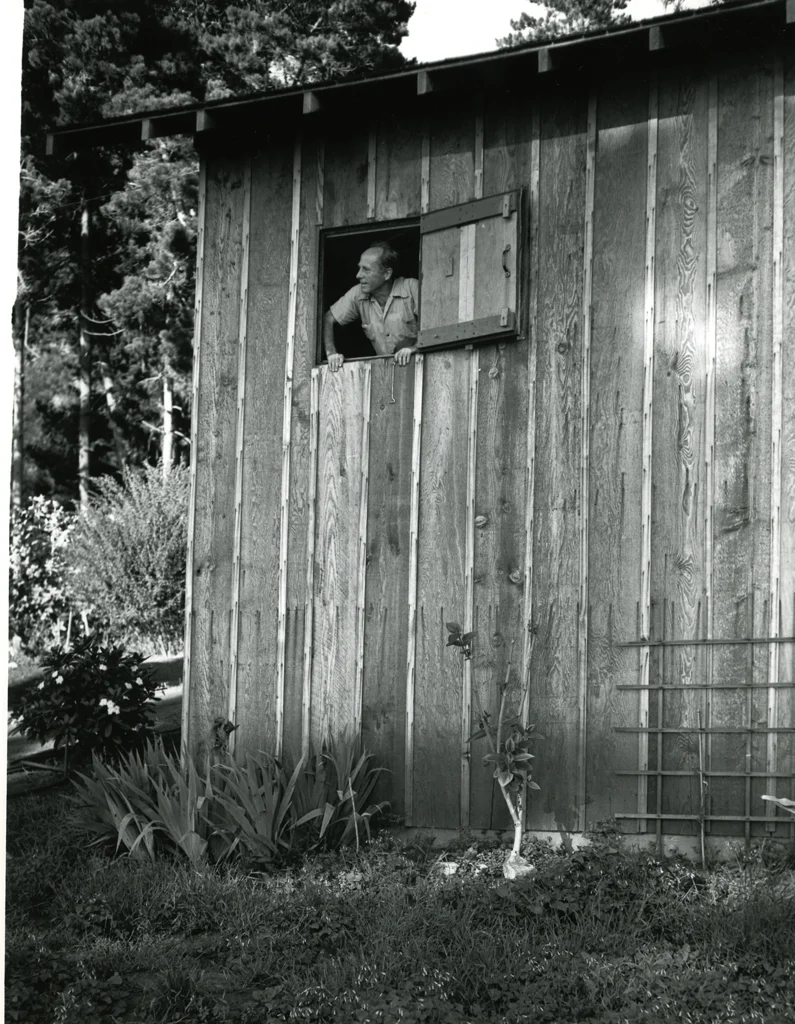

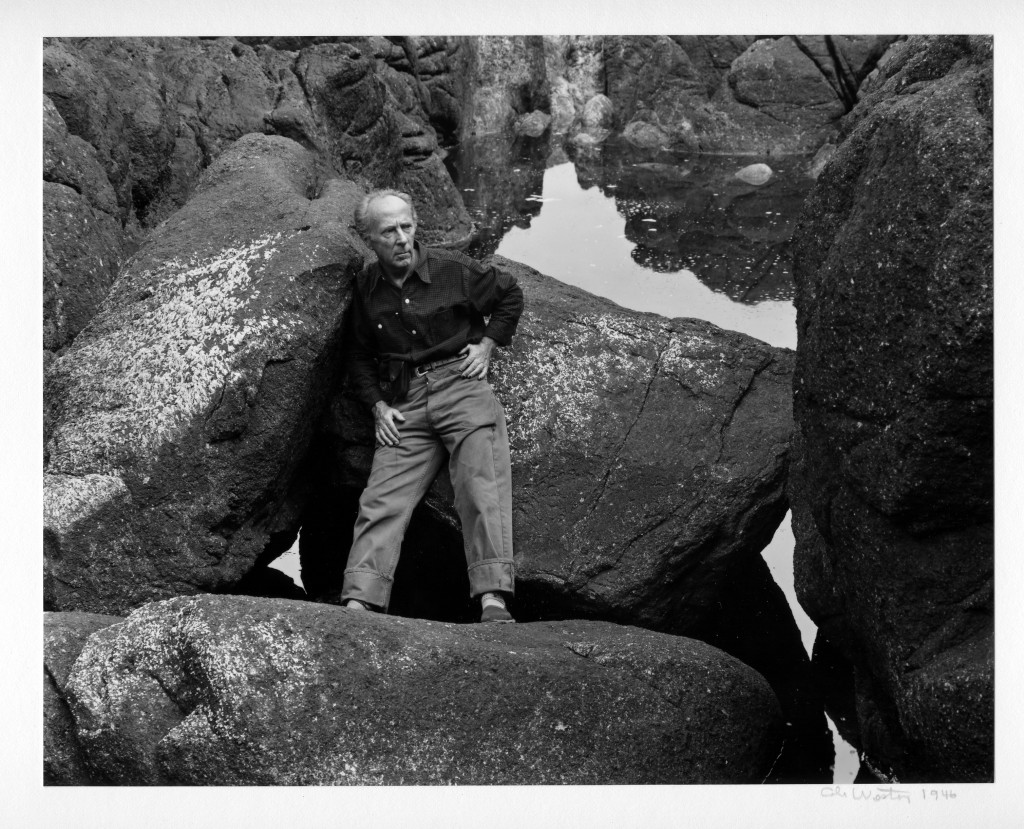

The real Edward Weston is a humble family man and a photographer of unequaled talent. He was dedicated to his four talented sons, devoted to his sister, Mary and eternally passionate toward his collection of friends, students, and lovers. This picture is considerably less romantic but clearly more accurate and appealing. After his death, his second wife Charis Wilson, expressed shock and dismay at the cliché-ridden myth that had been created to replace the flesh-and-blood man that she knew as Edward Weston. This exhibition delves into Edward Weston as brother, son, and father, the man “a robust lover of life…a man who found the world endlessly fascinating.”

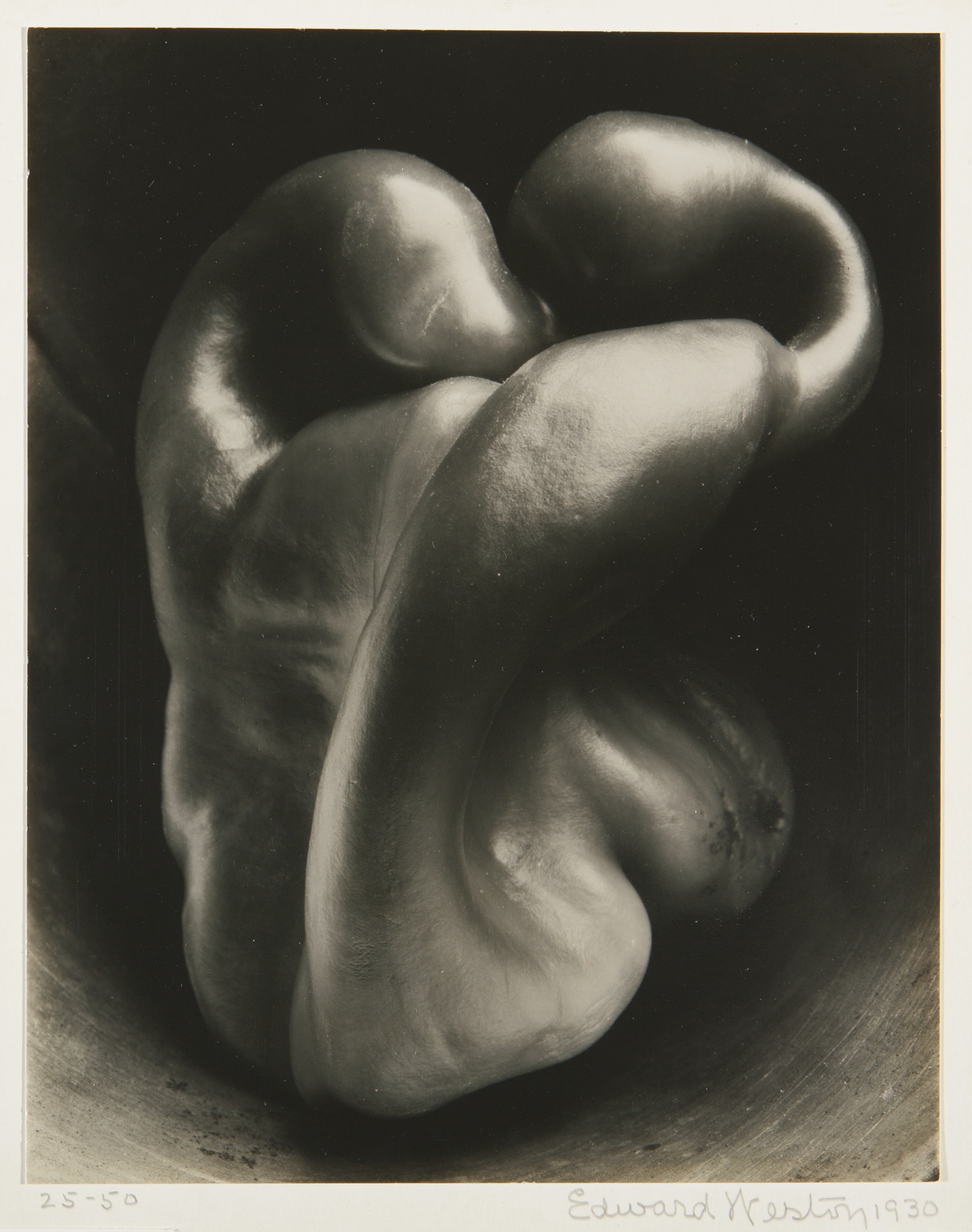

Weston’s mastery of photography is unparalleled. In a review of the traveling exhibition Edward Weston: Photography and Modernism at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Washington Post art critic Henry Allen wrote, “Through no fault of his own, Weston’s discoveries have become clichés. After all the imitation and reproductions, you can’t quite see his work for what it is, or was. But what wonderful pictures they are, when you stop thinking about them. The eros of the pepper, the classic purity of the chambered nautilus, the gleam of an ocean wrinkled like molten metal: No one had done what Weston did, and a lot of people have tried.”

We think we know Edward Weston. His Daybooks provide a lengthy insight into his daily wanderings through a dozen of the most productive years of his career. Numerous books – some written by Weston himself – address his life and work. Weston’s voluminous correspondence complements his Daybooks to round out an amazing archive of primary source material. And, because Weston began writing early in his career, publishing an article in 1911 in Photo Era that would presage his prolific production as a writer on his own work, the world was given as window on the mind of this man behind the myth. But do we really know him?

At first glance, the ocean of correspondence, journal entries, and other writing by Weston and about him is vast. One can easily wonder, “How could an artist be so verbose, so articulate, and so introspective about his work, his career, and his life, yet be so misunderstood?” In reality one needs to look more carefully at this body of writing to extract its underlying meaning – Weston’s translation of life’s every day trials and triumphs – to see what sparked him. One also needs to recognize that, like most people, Edward Weston changed and matured throughout his life. Weston the portrait photographer of the middle teens is vastly different from the Weston that journeyed to Mexico a few years later. And this Edward Weston is altogether different from the sated, mature artist who was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1936.

The epicenter of his published work, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, relates to little more than a decade of his nearly half century career. This was a time, one should note, that was replete with many personal changes in his life: confrontations with his first wife, Flora; his prolonged sojourn to Mexico and separation from his beloved sons; and then his wanderings in California. This expansive and introspective journal – it is an impressive two volume set – ends shortly after he meets Charis Wilson and settles down more permanently in the early 1930’s in Carmel, California.

Because our viewpoint today has been clouded by the passage of time and compounded by the natural complexities of human nature, we tend to see a distorted view of Weston through the murky lens of history. Time has passed, memories are faded or lost, and legend supplants truth.

A CLICHÉ-RIDDEN MYTH . . .

Charis Wilson, Edward Weston’s second wife and partner through his wonderfully productive 1930’s and the war years, remarked that she was shocked by the cliché-ridden myth he had become in the hands of his biographers and other writers. She blamed his distorted image on their sources of impressions, particularly his Daybooks, with their many limitations and a point of view Weston himself later lamented. By his own admission, Weston thought his Daybooks did not truly reflect all that he was engaged in emotionally as well as intellectually. He found them full of “immature thoughts” and “excess emotions.” Weston admitted, “I find far too many bellyaches; it is too personal, and a record of a not so nice person. I usually wrote to let off steam so the diary gives a one-sided picture which I do not like.” For Weston, his Daybooks represented “doubts, certainties and constant growth. They were a way of learning, clarifying my thoughts.”

The myth of Edward Weston has grown dramatically during the past decades. Art historians, critics, and even friends have helped to perpetuate the image of the dark and brooding artist. The problem has persisted for decades.

“The myths about my father are legendary,” his youngest son, Cole, exclaimed. “He was not apolitical. He was very athletic, loved to watch football. He loved to watch boxing. When I was very young I remember them well. We stood outside with a small radio to listen to the Dempsey-Tunney fight. He was a runner. He would take us down to Carmel Beach and beat us all.” Weston’s sons’ memories are certainly replete with photography, but it is their memories of their father as “dad” that come to the discussion with the greatest passion and enthusiasm.

Visiting the behemoth retrospective exhibition of Weston’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1975, a New York Times art critic found his work to be “static, indrawn, remote and sometimes morbid.” This critic, like so many others since then, read his Daybooks, his biography, and a variety of other sources. From these were gathered an initial impression of Weston as a “vital and virile romantic who lived a life of physical simplicity and emotional richness” – a very accurate picture. Yet upon reading the Daybooks and the biography, the critic found herself remarking, “One’s sense of Weston darkens; one gets the feeling that he didn’t enjoy himself very much (What artist does?). He was happy at the start of a love affair (‘The idea means more to me than the actuality,’ he confessed, and pondered, ‘Is love like art – something always ahead, never quite attained?’).”

This analysis concluded that the Daybooks expressed Weston’s “anxiety and loneliness and eccentricity that underlay and undermined the surface exuberance and gregariousness and conventional bohemianism.”

The classic misconceptions of Weston and his work focus on his images of natural forms such as the shells and peppers. Many art historians have interpreted Weston’s Nautilus Shell and his Pepper No. 30 as suggesting sexual repression. One critic noted that it “reeks with sensuality.” They contended that the work had a “double meaning, reminding us of the double life that Weston was leading, making portraits that embarrassed him, constantly unfaithful to his lovers, never having time to be the good father to his sons that he had hoped to be.”

These were opinions Weston vehemently denied. Weston stated more than once, unequivocally, that such viewpoints were both surprising and incorrect. “I am not sick and was never so free from sexual suppression . . . I am not blind to the sensuous quality . . . No! I had no physical thoughts, – never have. I worked with clearer vision of aesthetic form. I knew that I was recording from within, my feeling of inner life as I never had before.”

Another historian claimed Weston’s kelp pictures were “sinister and dark,” while his shell rears “like a sea monster.” This harsh interpretation was taken even further, labeling Weston’s peppers, kelp, and fungi to “hint at a turbulent, even demonic imagination.” Those who knew Weston, especially his children and Charis, would absolutely refute this perspective. Little in Weston’s voluminous output of writing supports this speculation. But the myth of Weston continues to build.

The criticism of Weston extends further, attacking his basic motivation. Some have claimed that Weston’s was “an extremist art” and that he was “drawn to whatever was most alienating, to extremes of desiccated and abandoned landscape . . . working always with regard for the twin poles of fullness and desiccation, life and death of the senses.”

Even when art historians have tried to place Weston in context, they have often perpetuated the same myths. In one case, Weston was branded a “loner and solitary genius.” This clearly ignores the fact that his family, collaborators, lovers, and others often surrounded Weston. On his two-year-long Guggenheim travels during 1937-1938, Weston was almost always in the company of Charis Wilson and often one or more of his sons, usually in relatively close quarters – hardly the attributes or living style of a loner. Weston was, in fact, a gregarious and outward-looking person who craved solitude as a respite from those many moments he was surrounded by others.

Weston’s late years as a photographer were subject to further misinterpretation. His works from the 1940’s, including his commission from the Limited Edition Book Club for a volume on Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, have been condemned with a “sense of age and aging . . . Old places, old things, old faces settle into an impression of inertness . . . Landscapes heavy with clouds seem brooding.” Damned as “funeral or elegiac,” it has been questioned whether “Weston’s changing state of mind” was the cause, referring to the serious marital difficulties he and Charis were beginning to experience, compounded by the uncertainties of war, which broke out in the middle of their Leaves of Grass journey.

In an essay describing Weston’s late landscapes, one art historian contended that beginning with his Guggenheim fellowship in 1937, “and perhaps without the artist reading it – the subject of Weston’s photography became Death.” (Note that this is death with a capital “d” and that Weston himself may have been oblivious to this preoccupation that is apparent to so many others). This tangent was taken even further when Weston’s intention to fulfill his Guggenheim obligations with images “photographing Life” was described as “in retrospect, ironic.” Once again, critics read death into Weston’s work as a primary subject matter: “a burnt-out automobile, a wrecked car, an abandoned soda works, a dead man, a crumbling building in a Nevada ghost town, long views of Death Valley, the skull of a steer, the charred remnants of a forest fire, gravestones, and the twisted, bleached bark of juniper trees – a virtual catalogue of decay, dissolution and ruin. [emphasis added]” Critics have referred to his late work at Point Lobos as a “veritable theater of death.” However, according to this same critic, there are “enough pictures of ‘innocent’ subjects – dunes, cloud studies . . . to suggest that Weston was not exclusively preoccupied with death.”

Earlier, in a review for the Weston retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1975, one critic had applied a psychoanalytical approach to his work. He noted that dark elements – “caves, rocks or simply heavy shadows – occur with sufficient frequency in Weston’s photographs after 1937 that may be said to comprise a motif . . . the motif . . . comes to suggest death.” The critic journeyed into this psychoanalytic interpretations of his work out of hand. The critic found his rationale to do so in Weston’s strident denials, which “are what make the interpretation of his images so tempting.”

Although it is correct that these subjects signaled a change in his theme and style, in no way were these “new additions to Weston’s artistic repertory.” Weston’s work with death in Mexico more than a decade earlier is ample evidence to this fact. Moreover, to contend that his final work constitutes a “theater of death” ignores his entire body of color work, which is full of light, color, and life. The contention that Weston became a brooding, dark, and morose individual in the last years of his life is, at the very least, highly misleading, and at worst, just plain incorrect.

Charis Wilson says this narrowly focused image of Weston is further exaggerated by accounts of him in his final years, when he was suffering the debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease and was no longer the “robust lover of life he had always been.” Lost was the “man who found the world endlessly fascinating.”

Even his longtime friend and collaborator, the art historian Nancy Newhall, who edited his daybooks for publication, was lulled into furthering these misconceptions. She claimed “he never laughed out loud,” a notion adamantly refuted by Wilson, who recalls “many an uproarious bout of laughter.” For many who knew Weston late in his life, they only remember the man beset with the ravages of Parkinson’s that left him a shadow of his former self. Forgotten are the numerous accounts of laughter, dancing, and merry-making. Weston claimed, “A good laugh is cleansing.”

It’s fortunate that not every photo historian and critic has taken this tack. The renowned curator and author John Szarkowski attributed Weston’s later inspirations to illustrate a “new spirit of ease and freedom” rather than a morbid focus on death and decay. He concluded, “A sense of the rich and open-ended asymmetry of the world enters the works, softening their love of order.” The noted photography historian and educator Peter Bunnell referred to Weston’s struggle with identity and his quest for intellectual wholeness as an underlying motivation for his remarkable ability to reinvent himself and his work several times throughout his career. This personal journey, rather than any of the various described preoccupations, was at the root of his influences. Bunnell also criticized the myopic focus other writers had on Weston’s love interest and the “narrowly dimensional characterization of Weston” that had skewed the public’s perception of the artist.

The insightful photographer and author Robert Adams summarized it best when he chastised recent biographies of photographers as being based on little more than gossip. Adams says he hopes for a biography that looks to Weston’s inspirations: “I think they did not necessarily come from the sometimes foolish man who was a vegetarian but enjoyed bullfights, the one who believed in astrology and wore a velvet cape. They must have come from a more thoughtful person who suffered enough to learn.”

Adams may have come closest to the truth when he claimed “The importance of the last pictures seems to me not so much that they show Weston’s awareness of death, but that they demonstrate the personal achievement of which Beaumont Newhall wrote after seeing Weston in a late stage of his illness: ‘He accepted his fate and was resolved to bear it.’ The progressively relaxed compositions of his later pictures testify to a willingness to affirm life on other than selective terms. They show the peace that is evident in his last letters to friends, letters as beautiful as any of which I know – brief, colloquial, dignified and urgent with affection.”

Adams contended that, “running through much of Weston’s life was an engaging spirit of celebration, and that also grows in the late Point Lobos pictures . . . I think I see it in the photographs – a new sensitivity to light, to light just in the air, especially to light as it is caught by shooting into the sun.” Rather than harkening to the “dark side” of Weston, Adams correctly concluded, “He appears to have become, after many failed attempts, another person, growing away from his earlier egoism and its disappointments toward a more generous view of other people and the world as a whole.” If this is true, and a careful examination of Weston as the father, brother, son, husband, and friend will attest to this fact, the image of Weston needs an appropriate rejuvenation.

MY GREATEST INFLUENCE . . .

For Weston, his pure aims in photography were inseparable from his philosophy of life and living. He articulated this well in a classic line he penned to Henry Allen Moe at the Guggenheim Foundation as an addendum to his application for a fellowship in 1937:

My work-purpose, my theme, can most clearly be stated as the recognition, recording and presentation of the interdependence, the relativity if all things – the universality of basic form . . . In a single day’s work within a radius of a mile, I might discover and record the skeleton of a bird, a blossoming fruit tree, a cloud, a smokestack; each of these being only a part of the whole, but each – in itself – becoming a symbol of the whole, of life.

Although Weston was keenly aware of photography’s history and its renowned practitioners such as Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, and Charles Sheeler, about whom much has already been written, his most important influences and inspirations were, interestingly enough, outside the bounds of the field. Weston was, in his own mind, first and foremost, an artist. He credited his true influences to all art forms. “To increase one’s art appreciation, literature, music, drama, and other arts are as important as the study of pictures, perhaps more so, for the former would not tend to influence one into merely copying other work,” he wrote in 1917. Responding to a criticism from Stieglitz that he had not been an influence in Weston’s life, Weston took time to reflect on what his most outstanding “inspirations” in his life and upon his work were:

I feel that I have been more deeply-moved by music, literature, sculpture, painting, than I have by photography, – that is by the other workers in my own medium . . . seeing, hearing, reading something fine excited me to greater effort, – (“inspires” is just the word, but how it has been abused!). Reading about Stieglitz, for instance, means more to me than seeing his work. Kandinsky, Brancusi, Van Gogh, El Greco, have given me fresh impetus: and of late Keyserling, Spengler, Melville, (catholic taste!) in literature. I never hear Bach without deep enrichment, – I almost feel he has been my greatest “influence.”

Weston’s camera was a conduit to understanding life and allowed him to capture what he considered its very essence. Describing his work in detail, Weston gave us insight into his philosophy: “The majestic old boats at anchor in an estuary across from San Francisco . . . the full bloom of Miriam’s body – responsive and stimulating – the gripping depths of Johan’s neurasthenia – the all-over pattern of huddled houses beneath my studio window on Union Street – in these varied approaches I have lately seen my life through my camera.” Weston himself relished in these descriptions, and they motivated him to greater heights. In a review of an exhibit in 1931, a critic wrote, “But in Carmel, we find him moving beyond the artist. It is here that he has transcended art and become a seer. Seen through his eyes, the concealed flight in the wing of a bird, the sculpture of a bud, is transformed from things seen to things known.”

For Weston, beauty mattered. It was an indispensable part of life. Moved by the landscape, a stony outcrop on Point Lobos, or the crumbled remains of a ghost town, Weston sought beauty wherever he looked. “I am ‘old-fashioned’ enough to believe that beauty – whether in art or nature, exists as an end in itself: at least is does for me.”

Nyerges, Alexander Lee. “Edward Weston: Lover of Life.” Edward Weston

A Photographer’s Love of Life. Dayton, Ohio: The Dayton Art Institute, 2004. 21-93. Print.